The continuing adventures of Australian Designer William Constable in the world of UK horror films.

Bob Hill – May 2022

In an earlier article I wrote (Dec 2018) for the APDG on legendary artist, illustrator, theatre, ballet, Opera, TV and film designer William “Bill” Constable (1906 – 1987), I left him heading off to Great Britain, (in the words of Australian Oscar winning set decorator Ken Muggleston), ‘wanting to become famous’. He may not have quite achieved it, at least on an international scale, but he did eventually attain a lasting fame among the cult world of Dr Whovians and fans of the cheapest of cheap Sci Fi films ever made in the UK – Amicus Pictures.

As many historical commentaries on Bill Constable have often noted, Bill’s energy and output were prodigious, to say the least: A polymath of the first order who designed literally dozens of ballets, theatre sets, TV series and feature films as well as illustrating books and holding multiple exhibitions of his paintings, his design skills were built from his early training at both the Victorian College of the Arts in the 1920s and later at the lauded Academy of St Martins Art School in London in the early 1930s.

Long regarded as Australia’s premier theatre and ballet designer, Bill was given the call at the age of 47 to Production Design his first feature film – the UK/US production of the “Long John Silver” at Sydney’s Pagewood Studios in 1953, (see the APDG archived story, Dec 2018), where he appears to have completely caught the film bug.

The dashing Bill Constable and his extremely capable assistant Desmonde Downing working on designs for “Long John Silver” at Pagewood Studios, May 1954

Though he continued to design for ballet and theatre following his debut in film, with no Australian film industry to speak of in the mid 1950s and only occasional jobs on UK and USA productions available through Pagewood Studios (Pagewood veteran Lex Meredith recalled him painting a huge realist backdrop in the studio – possibly for “Smiley” in 1956), Bill may have taken the advice of his former patron and employer, Edouard Borovansky … and headed West… i.e. back to London, where he’d first struggled to make a design career in the 1930s.

Upon his return in May 1957 and with the Long John Silver Production Design credit as his calling card, Bill quickly found his way into the burgeoning British film production scene; It was the period of US cinema distribution money being laundered out of the UK in the format of quickie films & TV series*… and Bill scored his first major credit on a standard Black & White spy thriller called “The Secret Man”. Despite its lowly credentials, at least this time Bill was working in film, even if it was a quickie; It’s worth noting that his IMDB credits for “The Secret Man”, list him as Production Designer; other documents list him as “Set Designer”… which in those days, along with the old title of “Art Director”, was pretty much an interchangeable job description. There are a couple of standard sets in the film and a lot of grotty locations, and since it was shot in and around a grimy London still recovering from the war, the final result was as murky looking as might be expected. Still, it has a lot of classic overweight & underpowered English car brands such as Vauxhall, Hillman Humber, Vanguard, Rover and the inevitable Ford Anglia poking around English streets and country lanes – all doing their best to look like cold war spy transports:

- It’s a strange fact of life the classic English TV series “Robin Hood” (1954 – 55) was written by blacklisted US writers and shot in the UK – as much to avoid McCarthy era bans on US TV, as to save money.

Snipe. Top speed, 70 mph downhill: as seen in “The Secret Man” 1958.

(You can tell it’s a spy film by the trench coat)

Bill next scored Art Direction/Design duties on an episode of another UK/ US produced cold war spy adventure – a TV series entitled “Behind Closed Doors”, that featured even more second-rate American actors in a low-cost production designed to feed a massive demand for TV series abroad.

A Brief Diversion – Back to Ballet

At the same time Bill’s theatre world connections led him into designing the setting for Noel Coward’s only ballet – a short work of some 35 minutes entitled “London Morning”. The conventions of the era were for a huge painted backcloth… with fly wings and some foreground physical elements such as columns, arches, benches and staircases etc…. all set within a decorous proscenium arch.

The only extant image from “London Morning” shows a sketch for the backcloth (which Bill would have painted himself)… but apparently Noel Coward loved the result!

London Morning 1958 – backcloth design

Noel and Bill

However, it was to be Bill’s only foray into theatre during his 15 year UK career, since film was waiting to claim his full attention… starting with a major art direction role on the prestigious production “The Trials of Oscar Wilde” 1960.

“The Trials of Oscar Wilde” 1960 … the Ken Adam Connection.

A padded-up Peter Finch as Oscar reclining in Edwardian splendour with Bosie. A fellow Australian, Finch shared first prize for “Best Actor” at the 1961 Moscow International Film Festival

The credits for this comparatively cheap (just £15,000 allocated to the sets) and rushed film, (there was another Oscar Wilde film in production at the same time), state that the Production Designer was the legendary Ken Adam, who was later to win Oscars & international renown for Kubrick’s “Dr Strangelove” and the definitive Bond Films. Bill Constable is credited as “Associate Art Director”… which would suggest he had a much greater creative role than chasing up the construction crew and keeping the art department on schedule and on budget. In an exhaustive interview biography of Adam written by Christopher Frayling (2005), Adam discusses how he drew all the sets in pen and ink and watercolour … and since the film was to be in Technicolor, placed coloured gel over some of the drawings to serve as a lighting and mood style guide. The plush interiors certainly reflect this aesthetic.

At the 1961 Moscow International Film Festival (an important event at the time – Visconti was President that year), “The Trials of Oscar Wilde” played in the Competitions and received multiple Silver Awards… among them for “Best Production Design”… which was given to “Set Decorator Bill Constable and Costume Designer Terence Morgan”. Since Bill was a consummate draftsperson, it is probable that he did all the grunt work drawing up Adam’s stylised Victorian designs, whilst running the art department and decorating the sets in flawless Edwardian detail. In Frayling’s book, Adam confirms that Visconti “… gave me the first prize for best design…” but there is no record of his name appearing in the Festival program – just Bill’s. Ken Adam designed three films that year, which begs the question did he just start the film… and then head to greener pastures, leaving most of the production work to his “associate”?

The First (and only) South African Spaghetti Western:

For his next adventure, Bill picked up another project that Ken Adam had started a year or two earlier – “The Hellions”, a bizarre co-production between South Africa, the USA and Great Britain. The film that was eventually shot in a dusty South African town was a hybrid of dodgy money and B list South African and British actors – including an aging (& short) male hero, a minor pop star and “the producer’s girlfriend in the lead”. It’s described today as “South Africa’s first genre western”… and might still be its only one!

Credited as the Production Designer, Bill created a substantial street set and managed to evoke a convincing western location worthy of Texas. Although Ken Adam had originally designed and built a model of the set before switching to “Oscar Wilde”, it’s unknown if Adam’s designs were used, re-worked, or if Bill started from scratch… but either way, the final result is realistic and impressive. Despite being called “High Noon on the veldt… widescreen drivel” by the New York Times”, the movie did ok business on its release in 1962, but the weird mash-up of accents and the South African setting make it a very strange film…

The Title sounds much better in Italian!

1961: “The Playboy of the Western World”: Credit – Art Director

Synge’s classic play was always going to be filmed in Ireland… and in early 1961, Bill Constable headed off to County Kerry to build whitewashed, thatched roof stone cottages on a beach at Dingle. His designs have a certain affinity with his Long John Silver sets – being period, rough-hewn and a little on the theatrical side. In building his cottages and interiors, he used many local labourers and crafts people alongside his own art department team… and the results are excellent and authentic renditions of a remote community in Western Ireland at the turn of the 19th Century:

1962- 64 saw Bill working on several major films as “Assistant Art Director”, or “Associate Art Director” and sometimes uncredited. Notable amongst them was “Scream of Fear” (wheelchair bound girl in a creepy mansion) and the international Viking blockbuster “The Long Ships”… another Ken Adam castoff…for which Bill is credited as “William Constable, Art Director”. He possibly designed all the interior sets (dungeons etc) in the UK and is reputed to have also designed the main town… shot, of course, in Croatia (warmer than Norway!). Bill is the only English art director credited… along with a group of Croats who apparently could outdrink anyone. The remnants of the village stood until very recently as a tourist attraction:

However, for his third film in succession following Ken Adam’s footprints, the question arises once again… were these Adam’s designs from some years earlier when he recced Dubrovnik and did preparatory design work for the same production?… or were they all Bill’s? In the Christopher Frayling interview, Ken Adam relates how he told the Producer (Irving Allen) that the place was full of palm trees and “You’d never get a palm tree in Norway”… only to be told “Who cares? A tree’s a tree!”. Croatia and Morocco remained the locations for the shoot… and Ken Adam’s name is totally absent.

1963 – 1964: William Henry Archibald Constable flies solo

Following his time designing Viking worlds, Bill was commissioned as an “Associate Art Director” to work on the prestige production of “Lord Jim”… starring “Lawrence of Arabia” superstar Peter O’Toole as the titular character. The film was ultimately a limp flop and the timeline and backstory is now muddled, but it received a BAFTA for Best Production Design – which went to Geoffrey Drake, without a mention of Bill anywhere. However, it seems Bill spent some 9 months in Malaysia and Cambodia recceing and designing location sets for the highly anticipated movie – and privately staying on to tour Cambodia and paint. Although uncredited in the IMDB listings, Bill certainly contributed to the movie: The wharf scene shot in Malaysia matches his set painting and several set sketches and an extensive file of location photos and plans from the film are included in the Constable archive at the NGA in Canberra. Bill’s daughter is quoted in “Dr Who Magazine” as saying “that film was pivotal to Dad, he was Production Designer going out early to look for places and to design the sets.” Despite the fact that Cambodia was virtually a war zone (the Vietnam war was next door) and a lot of hostility towards Europeans was evident in the country (and the film crew, according to a Peter O’Toole interview in 1970), Bill still went on a solo painting and drawing expedition to Angkor Wat. At heart he was an artist who, in the words of his daughter, just wanted to get out and paint”. However, he came back broke to London and he needed a job, fast…

Bill, meet Milton…

A previous foray into designing a minor teensploitation musical a called “Just For Fun” had introduced Bill to the man for whom he would go on to art direct/design 13 films in the next 6 years – the wildly enthusiastic producer, film buff and King of low budget horror and anthology films, the US born expatriate, Milton Subotsky.

Milton was not just a film buff, he also behaved like one… he read and consumed any trash sci fi, horror comics, gothic crime tales and anything in related genres he could get his hands on. Over the years as head of Amicus Productions, (Latin for “friend”… but probably a tip of the hat to Frankenstein’s monster introducing himself to a young victim in the 1931 classic), he churned out as many stories and scripts in the exploitation mode as anyone in Roger Corman’s stable. The only difference between himself and Roger was that he believed he was making great art … or at least commercially viable great art. With a business partner taking care of the finances, Milton was left free to create any films he wanted – as long as they made money for the distributors who backed them. In his lifetime he wrote dozens of original screenplays, short stories, adaptations and re-wrote many other scripts and treatments … whilst producing 43 films! In fact, Milton became the complete Anglophile. He even married an English academic psychiatrist… whose profession (and his wife’s library of psychiatric books) often featured in his films.

It didn’t seem to matter that a project’s logline and synopsis was insane, Milton went at it with both barrels: It takes a certain kind of genius to mash together the nascent teen pop star genre with a bizarre toy doll craze… but Milton did it with “Beats Go Gonk”: look it up – the plot is too crazy to describe here…and the setting of a studio beach is literally so bad, it’s headed into Ed Wood country. The players and pop stars in the film seem to get the joke… which makes it a fascinating curio today… not to mention that it’s filled with amazing musicians such as Hendrix’s future drummer, Ginger Baker, and others.

It didn’t take long for Milton to recognise Bill Constable’s ability to design quality sets – and, probably more importantly, stick to a budget. For Bill, the ride as Amicus’s go-to Designer was just beginning…

An admirer of Ealing Studios “Dead of Night” (1945), an anthology of 5 separate horror stories loosely threaded together by a gathering of the cast in a guesthouse, Milton Subotsky created a similar “portmanteau” film … with the simple logline “Aboard a British train, mysterious fortune teller Dr Shreck, uses tarot cards to read the futures of five fellow passengers”. Dr Shreck is, of course, Milton’s nod of the head to the silent masterpiece “Nosferatu”.

As each of the cast stories are revealed, the film opens out into various benign settings such as offices, cottages, a nightclub, a Gothic ancestral home… which then turn sinister with the addition of a werewolf, smoking coffins, a vampire wife… a disembodied creeping hand … voodoo and vines that strangle people!

Christopher Lee…

… warming a creeping hand by the fire

Poor gardening practices

Donald Sutherland administers a sleeping pill to his new wife

Featuring an exceptional cast (Peter Cushing as Dr Terror, Christopher Lee and a very young Donald Sutherland – whom Milton secured for the bargain rate of £1,000) the film was shot at Shepperton Studios using stock flattage configured to Bill’s functional set designs; it was both a critical and financial hit.

On a roll from “Dr Terror”, Amicus and their now favourite Art Director were about to enter cult fandom…

A sure way to get into a fandom cage fight, is to try and arrive at a definition of what is Canon and Non-Canon Dr Who…

Amicus’ “Dr Who and the Daleks” is a look-alike, independent spin off from the series, but with a different Doctor (Peter Cushing)… who, following the release of “Dr Terror” in the USA, had more of an international profile than the TV Doctor (William Hartnell). Without going into specifics, there are many differences from the series and the films that followed… especially positioning the Doctor as a human figure, an ‘intrepid earthling’, rather than a time slipping alien. The Tardis is also defiantly an old school police box… and the Daleks are brightly painted, to cash in on the Technicolor shooting stock. They’re taller, a bit wider at the base, but still buzz around on flat floors like demented TV studio cameras (how did they ever get up stairs?) whilst forklift lights twirl on their domed heads. Toilet plungers still appear on the end of broomstick arms … but there’s also some with mechanical claws and guns that spit CO2 – and there’s a shitload more of them… well, actually 8 “hero” Daleks and 10 “extras” Daleks … made by the same company who did the TV versions.

“Exterminate… exterminate!”The BFI’s website gets it right in their summary of the film’s departure from the look of the TV series: The highlight of the movie is its look. While the television series remained in black and white until 1969, Dr. Who and the Daleks was made in widescreen format and Technicolor, and everything is drenched in lurid greens and blues. The palette, along with the soundtrack and the constant array of sound effects, is key to establishing the film’s wonderfully pulpy sci-fi atmosphere. BFI This “wonderfully pulpy sci fi atmosphere” was all Bill!

The earthbound suburban settings, before the film goes interplanetary, are bland arrangements of stock flattage and props… which is to be expected on an Amicus budget. Even the wallpaper looks pre ww2 and you can see why the characters are happy to move to outer space as soon as a Police Call Box lands in their studio back garden. Production in-joke: Dr Who at home reading Eagle & Boys World magazine featuring their classic sci fi comic “Dan Dare – Pilot of the Future”

No Production design to see here…

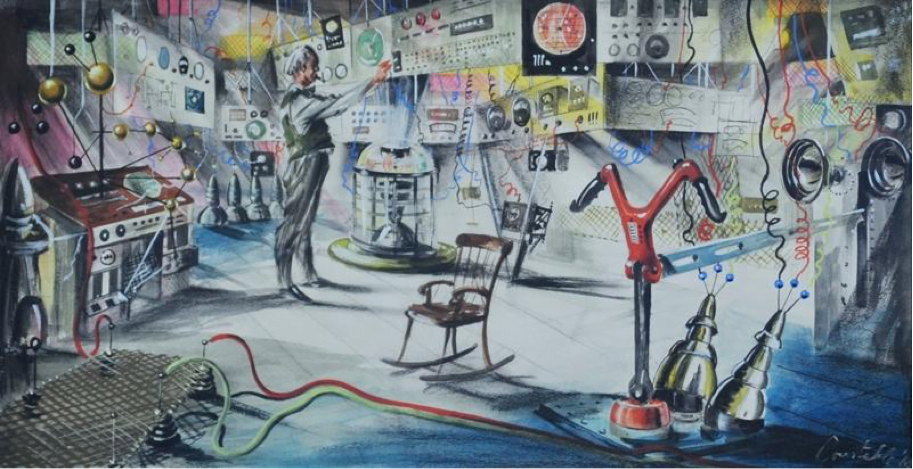

However, as soon as they enter the Tardis … Bill’s world comes alive: His original set design for the interior neatly connects to the character of the (human) Doctor Who… a tinkerer/inventor limited to using pretty much objects found on earth to create a chaotic space laboratory…

However, the reality of working on an Amicus budget reduced Bill’s post cubist design ambitions to rigging a tangle of wires, speaker parts, VU meters, a sun lamp, a couple of powerline insulators, sprayed balls, rods, and oscilloscopes – though a pared down version of the red control lever and the rocking chair remained!

The Petrified Forest Bill’s design centrepiece for Dr Who is actually a petrified forest – where the Tardis lands on a radioactive planet now overrun by humourless metal monsters. The trees were made from plaster … and designed to crumble at a touch… … and where they meet the planet’s dispossessed inhabitants in the forest – the wimpy Thals, who have possibly the worst haircuts and dye jobs in the history of science fiction movies…

Inspired by the intrepid Doctor, the Thals decide to reclaim their Dalek infested city by climbing a steep cliff face … glass shot…

Bill’s design…

The glass shot…

The actual set

Meanwhile, the Daleks are running rampant in the city they’ve taken from the bad haircut people… which owes more than a passing resemblance to a “TV studio/airport lounge meets 1960’s Las Vegas casino” vibe; Pastel tones, angular walls and backlit screens abound… Are the Daleks on the right playing the pokies?

… a lounge with a centre console that rotates!

Corridors were constructed from the new material of pink plastic…

A LOT of pink plastic. As Milton Subotsky told Kinematograph Weekly in April 1965: Our real star of the film is Bill Constable, who designed the sets. It’s probably the world’s first plastic set — it’s all plastic, but it looks metallic. We used all sorts of new materials.

Dalek friendly doors … and some scrunched up coloured foil

The film ends in a shootout where the Daleks are mashed and the Dr and his fellow travellers climb into the Tardis and leave… but not before they brush against what is undoubtedly the greatest British invention of all time (1963) – the LAVA LAMP! Bill was never going to miss this chance to include an up to the minute design icon!

Everlasting Fame: The film did good business in the UK (20th in box office rankings for 1965)… but not so good in the US where the TV series was unknown.

However, in that same year, the Daleks were loaded on a truck and shipped off to the Cannes Film Festival …

Where they met the 2nd most important British exports of the era – the Beatles!

BILL CONSTABLE PART TWO – Sci Fi, Bees and Brains

“What do you make of that then?”

“It’s a kind of vibrator. Can’t you feel it?” (“The Terrornauts” 1966 – actual dialogue)

In a fabulous article in “We Are Cult” magazine (2016), British film lecturer Laura Mayne digs into the archives of completion guarantors, Film Finances, to access the forgotten designs of Bill Constable’s next project for Amicus – “The Terrornauts”…

As the good Dr. Mayne describes it, the plot is as unhinged as anything Amicus had ever attempted previously:

“… ‘The Terrornauts’ follows the crew of Project Star Talk, whose mission is to send out radio signals in the hope of making contact with alien civilisations. Unfortunately for the main characters this hope is realised, and this culminates in the entire crew being kidnapped and held on an alien spaceship which is moored on a nearby asteroid. Most of the action takes place on the spacecraft, where the main cast are greeted by a colourful spiny robot who leads them through a series of tests to determine the sophistication of their reasoning faculties…”

After this enormously exciting premise, the reality of an Amicus budget (£87,000) kicks back in… with the chasm between Bill’s designs and the executed sets wide enough to think that it was a deliberate plot to destroy his career…

The reality (including ladders – on a space ship!) The film’s main protagonists come in for special design attention…

Alien creature concept art. (A tree stump with teeth and an eye?)

The truly terrifying critter as it appears on screen

Bill’s concept art for the Asteroid space station is actually pretty cool…

The model, well…

The attempted human sacrifice of the lovely Zena Marshall features some truly unique headgear –

… which seems to be a regular trope in Amicus’ sci fi films

… which seems to be a regular trope in Amicus’ sci fi films

The film was ultimately released on a double program with Bill’s next Amicus sci fi production “They Came From Beyond Space” … and is usually described as “the two worst films the company ever released”, with the director, Hammer veteran Freddie Francis, remarking in an interview “…the producers had spent all their budget on “The Terrornauts” so there was no money left over for They Came from Beyond Space” (IMDB).

They Came From Beyond Space – 1967 A miserable budget would never stop Production Designer Bill Constable from whipping up an ambitious spaceship interior that seemed to owe its aesthetic to angular Soviet space art from the 1950s… Bill’s spaceship… with supporting struts (for a machine that can fly through space?… and is that a built-in dolly track?)

The double bill flopped

despite some signature Amicus nifty headgear

Fabulous eyewear

a star shaped operating table…

And a truly great poster!

The Final UK Years

“The Skull” (1965) was a fairly standard Amicus horror… “a collector comes into possession of the Marquis de Sade’s skull and learns it is possessed by an evil spirit”… but it features one stunning set – an homage to the famous somnambulist scene from the silent masterpiece “The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari” (1920”). It shows what Bill could do if given the scope…

“The Deadly Bees” – aka “Hives of Horror” 1966

My personal favourite Amicus film!

“The Deadly Bees”, despite Bill Constable building all the farm exteriors and interiors in a studio, the film’s design displays a totally standard low budget “service the script” styling… allowing the true stars of the film to shine – Suzanna Leigh’s underwear and the aforementioned deadly bees. Rated only 4 on IMDB, this is a late night doozy – if you can stay awake for the bee attacks which are controlled by a lunatic mastermind etc. etc…

There’s a quote in IMDB trivia which reveals how the film’s secret, hi tech special effects were executed… (though it fails to mention the old “Bees on a sheet of glass in front of the lens” trick)…

The special effects for the bee attack sequences were quite simple. Often footage of swarming bees would be superimposed over footage of the actors and fake plastic bees would be glued to the actors. Some shots of swarming “bees” was actually footage of coffee grounds, floating and swirling in water tanks, that was superimposed over landscape footage.

Having been burned on their two space flops and now the killer bees, Amicus returned to their more standard horror films… taking Bill with them. “Torture Garden”, (written by Robert Bloch of “Psycho” fame), followed; it had a better budget since it was financed by Colombia Pictures, but the anthology formula of 5 stories was starting to date. Despite having android Hollywood starlets, a man-eating cat and a vengeful Steinway grand piano etc and yet another stupendous poster, … the film did only average business.

A standard issue spy thriller turned up next (“Danger Route”)… a film for a non-Amicus production company… and then back to a bizarre mash-up of horror comedy – “Scream and Scream Again”. It involves a serial killer who drains his victim’s blood… and contains elements of sci fi, James Bond, a police procedural and features villains that were changed from aliens to communists at the last minute… all wrapped up in a non-linear plotline that’s impossible to follow. It’s beyond weird, yet strangely engaging and it sort of works. The real disappointment, however, is that the three promoted stars Vincent Price, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee spend very little time on screen.

The Grand Finale – A Kickstarted Brain: “The Mind of Mr Soames” 1970

For his last film for Amicus… in fact, Bill’s last film ever, he designed the underrated “psychological thriller” curio “The Mind of Mr Soames”… which features an excellent cast, with Terence Stamp starring as a 30 year old man who has been in a coma all his life… until given an operation that will accelerate him into adulthood, whether he wants it or not…

The interior sets and the dressed locations that are seen when Mr Soames goes on the run from the hospital are both plausible and serviceable without being flashy or “look at me”… adding to the film’s mood of low-key realism. The operating theatre scene is especially authentic… with the film’s famed Cinematographer Billy Williams having gone on record (on the DVD extras) as having observed several real brain operations to get the lighting right. In fact, Billy Williams lit the whole film beautifully for its tone and visual aesthetic… but he’s helped by Bill Constable’s perfectly functional production design.

The film’s “scientific experiment gone wrong” theme is quite a common trope in this genre, but “Mr Soames” is somehow a much superior version of the Frankenstein Prometheus myth than it first appears. Despite underdeveloped minor characters – especially the few women who pop into frame – there is a sub textual message of scientific responsibility lurking within the film’s structure. It even allowed Terence Stamp, a brilliant actor just starting to fall from the top of his game, the freedom to choose his own pink romper suit costume when he goes on the lam from his minders…

By 1970, the English film industry that had soared so high in the 1950’s and early 60’s was starting to run out of puff. The overseas money had disappeared to more tax friendly countries, (like it always does), studios were closing down, less features were being made… and TV production was limited and tightly controlled. Huge numbers of crew were unemployed… including star technicians … and the future was now the domain of young mavericks who could ride the winds of generational change.

It would also prove to be the perfect time for the now 66 year old Bill Constable to stop spending all his life in dark studios and on bitterly cold locations and return home to the Australian sunlight and his paint brushes…

This article is an edited extract from a much longer study of “Lost Australian Film Designers”. Bob Hill, 2022